We hate Valve's Steam Controller because it's different

My stomach tied itself into a knot as I read the gaming community's first impressions of Valve's final Steam Controller. "It's cheap feeling," many of them said, "difficult and frustrating to use." Forum posts, tweets and reviews all bemoaned how different the touchpads felt compared to traditional analog sticks, accusing it of fixing something that wasn't broken.

The general consensus seemed to be that the Steam Controller was a mistake: A drastic, unnecessary step away from the tried and true layout of the 16-button, dual-analog gamepad standard. I felt betrayed and even a little offended -- but it wasn't Valve's experimental gamepad that let me down (I love that little thing), it was the gaming community that decided to turn a cold shoulder to innovation.

I took up the case with peers and friends, but felt like an unwelcome (but well-meaning) door-to-door evangelist. "If you'd just give it a chance," I said, "you might like it. The learning curve is great, but the rewards are greater still." My pleas were answered with awkward but polite rebuttals from folks who'd already made up their minds. I was arguing with walls. "There's no way it will ever replace a good mouse and keyboard," they all told me. "I'm already used to the Xbox controller, I don't need a new gamepad." First impressions are everything, and the first impression of the Steam Controller's always been that it's a weird, alien gamepad that shouldn't exist.

Think of it as the DVORAK alternative keyboard to the dual-analog controller's QWERTY

Despair set in as the figurative door hit me in the ass for the umpteenth time. I may disagree with their stubborn point of view, but I understand their complaints all too well. The Steam Controller boldly throws out the dual-analog input standard -- a gamepad configuration that's ruled the industry for almost twenty years. Simply holding it sets off muscle memory alarms that quietly whisper a powerful lie: This isn't right. To make matters worse, the Steam Controller looks deceptively familiar, making any failure to quickly master its haptic-touchpads all the more frustrating. This should be easy, we think to ourselves, but it isn't. Rationalization sets in: It must be the controller's fault; it must not be very good; it probably couldn't replace a mouse and keyboard anyway. I don't blame anybody for thinking this way, but it's wrong. It's all wrong.

Our mistake comes from thinking about the Steam Controller as a minor iteration of existing gamepad design theory. In reality, it's more of a proposal to replace that paradigm. Think of it as the DVORAK alternative keyboard to the dual-analog controller's QWERTY -- it looks similar and performs the same function, but remains an overhaul so jarringly different it requires weeks or months of training to fully master. The Steam Controller is no different: If one cannot overcome its odious learning curve, it's impossible to pass fair or objective judgement on its faults and graces.

My own journey to master Valve's peculiar gamepad gave me flashbacks of learning to game with a mouse and keyboard. I remember balking at the sensitivity of the cursor, aching for the comforting limitations of my outdated, keyboard-only FPS layout. My thumb's struggle to steadily aim using the Steam Controller's haptic touchpad directly mirrors my adolescent self's fear of losing control of Quake's mouse-based player camera. I loathed it, but eventually learned better. I didn't have a choice -- the gaming industry was moving forward with or without me. With the Steam Controller, it's different; there's no catalyst forcing players to challenge their preconceived loyalties to the mouse, keyboard and dual-analog gamepad. What they have now "works fine." Why bother?

I can't answer that for those who have already passed on Valve's reimagining of the PC gamepad, but I was desperate to understand the company's insane vision. Valve had spent years pitching a revolutionary new controller for Steam, its digital video game distribution platform -- the largest there is. They resisted normalizing that design every step of the way, reluctantly replacing the original prototype's touchscreen with standard face buttons and a single, token analog stick. I had to find out what was so special about this oddball gamepad Valve was building. It took awhile, but I eventually did.

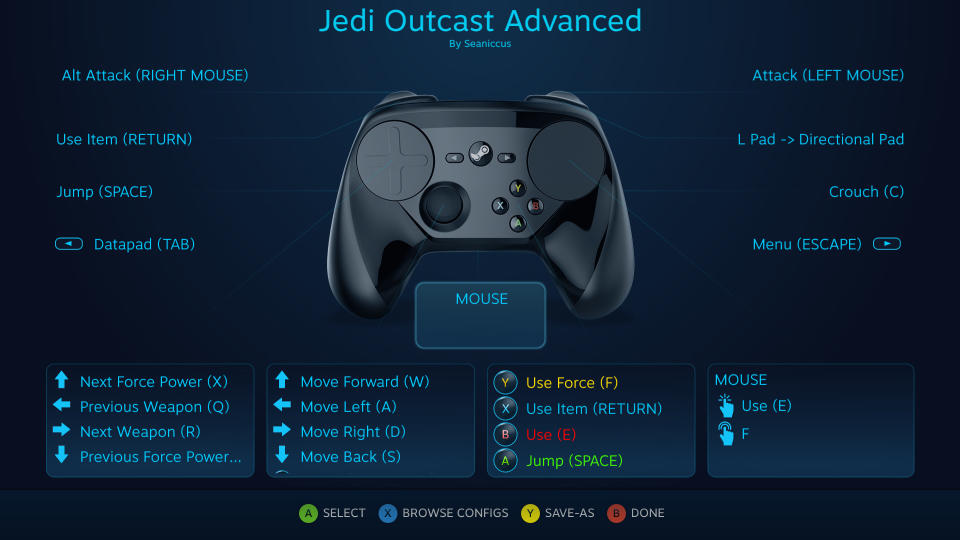

Learning to appreciate Valve's Steam Controller first-hand was a herculean effort. I had to unlearn decades of sense memory and teach my hands to embrace a touch surface that walked a blurred line between mouse, trackball, thumbstick and button. I spent hours experimenting with Steam's robust controller configuration menus, slowly unlocking the gamepad's hidden potential by tweaking advanced customization features. I forced myself to use only the Steam Controller for weeks, neglecting my beloved high-performance mouse and mechanical keyboard with optimistic guilt. This wasn't just an afternoon or two with the controller, it was an extended, wholesale embrace that helped me wrap my head around it.

I was angry at the gaming community for being closed-minded; furious that a "fear of change" was keeping evolution in controller design from flourishing

At some point, something clicked -- I had more control over the games I was playing than I ever did with a traditional gamepad. My thumb's quick flicks and the subtle aiming motions I employed to the controller's gyro sensor felt natural and nuanced. I felt more immersed, I realized, and I was having more fun. It's true, sometimes I had to dive back into Steam's controller menu to build a new profile or tweak settings (in fact, the best configurations are custom-made), but I finally understood why Valve was so confident in its bold, defiant gamepad. It's a better gamepad experience for me. I just had to master the device's core competencies to enable it.

I rushed to tell friends, peers and the internet of how I grew to love the Steam Controller, but soon learned I was a heretic. "The gamepad doesn't need to be fixed," I was told again -- and the suggestion anybody would ever choose a Steam Controller over the mouse and keyboard, even for casual use, is a statement so outrageous, it's almost offensive. How dare I challenge the status quo? How dare I accuse my friends of being afraid of change? How dare I suggest one learn how to use a radical new control device before passing judgement on it? I was rejected as an extremist, unable to see past his own dogma. I almost gave up.

For a long while, I was angry at the gaming community for being closed-minded; furious that what I saw as a "fear of change" was keeping a fantastic evolution in controller design from flourishing. Eventually, I realized my folly: It took me endless days and weeks to overcome my own first impression of the bizarre controller, but here I was trying to impart its potential on others in a matter of moments. Hadn't I already learned that it couldn't be appreciated without training? Again, I was reminded of learning how to type on a DVORAK alternative keyboard. It's impossible to understand its potential without having first learned to speak its language: I'm gaming at 60 words per minute on the Steam Controller; everyone I'm showing it to is under 15.

I'm not a fool, I know the Steam Controller has its faults, but its low-hanging face buttons and sharp plastic seams aren't likely to cause its downfall -- those imperfections can be fixed. Instead, the Steam Controller's potential to change the current controller paradigm is overshadowed by both the effort required to master the strange device and the prejudiced fear of change that challenge promotes.

It's the perfect PC gamepad for me: It's versatile enough to replace my Xbox 360 gamepad (I may never use it again), enable causal couch play for games never intended for the living room and it's made me think twice about using a mouse and keyboard in all but the most competitive or complex gaming scenarios. The Steam Controller is an amazing evolution in game control, but far too many gamers will never know. And all because change is hard.