Google algorithm lets robots teach themselves to walk

It's a milestone in making robots more useful.

There's no question that robots will play an increasingly central role in our lives in the future, but to get to a stage where they can be genuinely useful there are still a number of challenges to be overcome -- including navigation without human intervention. Yes, we're at a stage where algorithms will allow a robot to learn how to move around, but the process is convoluted and requires a lot of human input, either in picking up the robot when it falls over, or moving it back into its training space if it wanders off. But new research from Google could make this learning process a lot more straightforward.

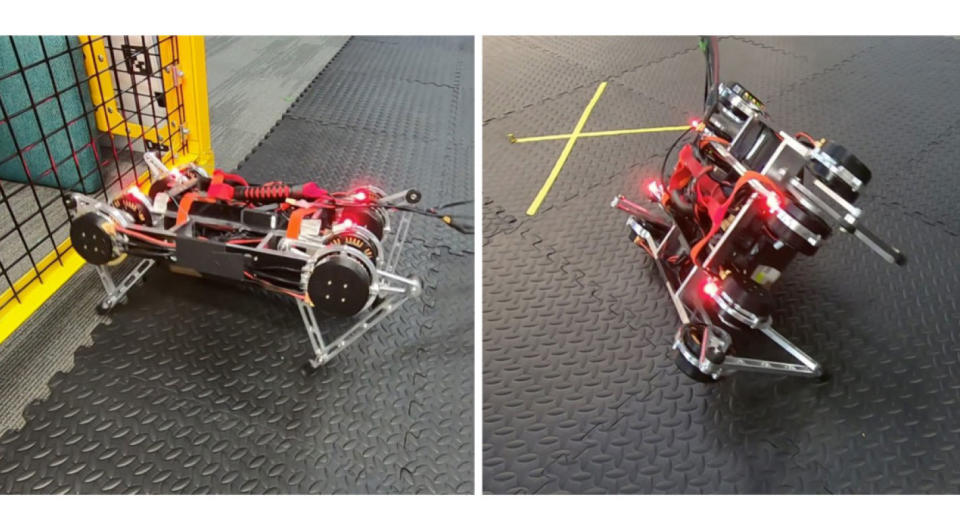

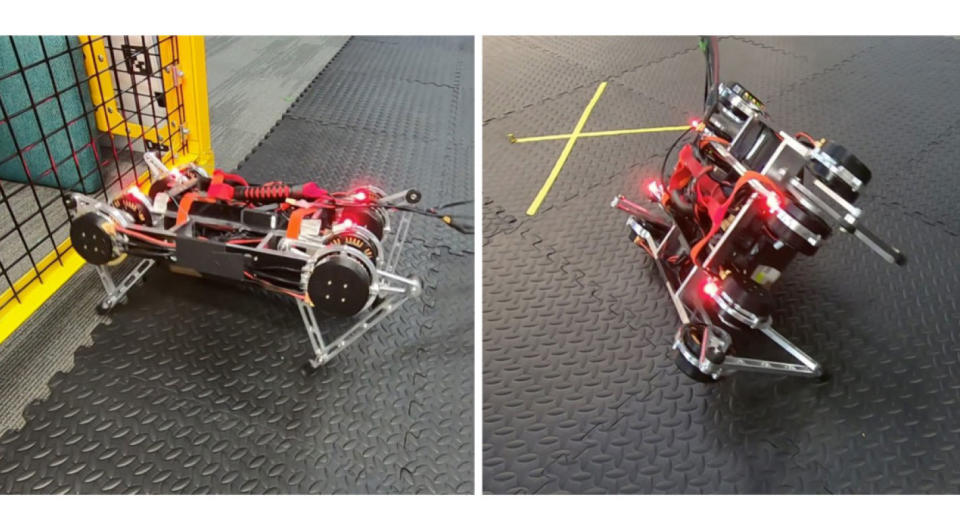

By successfully tweaking existing algorithms, researchers from Google Robotics were able to get a four-legged robot to learn how to walk forwards and backwards and turn, all by itself and in a matter of a few hours. First of all, they did away with environment modelling. Typically, before a robot gets the opportunity to learn to walk, algorithms are tested in a virtual robot in a virtual environment. While this helps prevent damage to the actual robot, emulating things like gravel or soft surfaces is extremely time-consuming and convoluted.

So the researchers began training in the real world from the get-go, and because the real world provided natural environment variation, the robot could more quickly adapt to variants such as steps and uneven terrain. However, human intervention was still necessary, with researchers having to handle the robot hundreds of times during its training. So they set about solving this issue, and did so by restricting the robot's territory and having it learn multiple maneuvers at once. If the robot made it to the edge of its territory while walking forward, it would recognize its position and start walking backwards instead, thereby learning a new skill while mitigating human intervention.

With this system, the robot was able to use trial and error to eventually learn how to autonomously navigate a number of different surfaces, ultimately removing the need for human involvement -- a significant milestone in making robots more useful. However, the research is not without its limitations. The current setup uses an overhead motion capture system to allow the robot to identify its location -- not something that could be replicated in any real-world robot applications. Nonetheless, the researchers hope to adapt the new algorithms to different types of robots, or even multiple robots in the same learning environment, thereby creating a body of knowledge and understanding that will help advance robotics in all fields.