Why FIFA Ultimate Team is often hated and very successful

The centerpiece of 'FIFA 21' is under attack from players, pros and lawyers. And it's more popular than ever.

‘See you in October’

An annual, anticipated ritual took place last month: The release of the world's most popular videogame of the world's most popular sport. FIFA 21 will no doubt make over $1 billion, as each entry in the series has in recent years. But the latest version of the iconic football (soccer, to Americans) simulator is only marginally notable for its minor aesthetic updates, niche gameplay tweaks or reheated rosters. To legions of FIFA players the new title really signals the start of a fresh season of Ultimate Team.

For the unfamiliar, FIFA Ultimate Team is the most popular feature in the game, and the one that's come to define the overall experience. It's the main game within the game. Premier League pros Sergio Aguero, Trent Alexander-Arnold and Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang play it. Essentially, you indulge the armchair expert's fantasy of building a dream team of your favorite players and competing with them against others'. Played over the course of real-life football’s autumn-to-summer seasons, it's Panini stickers or baseball cards crossed with fantasy football — and you get to play as your signings.

Fundamental to the game is opening loot boxes, known as packs — which consciously appropriate the Panini aesthetic — from which you acquire new, random players. The chance of receiving, say, Lionel Messi, is microscopic — but theoretically possible. You can earn packs in-game or purchase them with real money.

The effect is that Ultimate Team feels more like a freemium game lodged inside a $60 title. Everything that this entails is the nub of much dismay in the FIFA community. Yet there is still a buzzing industry of YouTubers cracking open pack after pack, Patreon accounts offering trading tips for the fluctuating in-game transfer market and illicit websites peddling virtual currency.

For publishers EA, it’s an absolute cash cow. Last year Ultimate Team modes in all EA Sports games — such as Madden NFL and NHL — made $1.4 billion. That's 28 percent of all EA's revenue, a company that also publishes Apex Legends, The Sims, and every new Star Wars game. Ryan Gee, an interactive entertainment analyst at Bank of America Merrill Lynch who has covered EA since the mid-2000s, estimates that FIFA Ultimate Team alone probably accounts for about $900 million. Having launched just over a decade ago as a FIFA add-on, Ultimate Team is now a cornerstone of the business model of one of the gaming industry's biggest players.

"There's only two games every year that sell 20 million copies: FIFA or Call of Duty," said Gee. Tim Sweeney, the CEO of Epic Games, has said that the only game that cuts into Fortnite playtime is FIFA.

This year's pandemic, which closed cinemas and concert venues and even nixed most live football for several months, has only benefited the makers of games that can fill the sports fan's void. Over the summer, EA said Ultimate Team revenue was up 70 percent from the same quarter last year, with 7 million new players. "This is off-the-charts different," said EA's COO Blake Jorgensen at the time. The pandemic is not about to end soon; analysts believe video game spending will only increase.

"There's only two games every year that sell 20 million copies: FIFA or Call of Duty" - Ryan Gee

So everything should look rosy for FIFA. Yet Ultimate Team seems to be under attack from every angle. Regulators in Belgium banned paid loot boxes — the only way that EA makes ongoing revenue from Ultimate Team — in 2018 , specifically investigating FIFA among three other games; the Netherlands recently upheld a €10 million fine against EA for violating gambling laws (EA has said it will appeal). Recent class-action lawsuits against EA in California and Canada claim FIFA loot boxes are essentially unlicensed gambling. The latest in a long timeline of EA's public controversies flared up just the week before the launch of the new game: a FIFA advert to spend real money on microtransactions in a children's toy catalog.

Most notable, though, is hostility from the players themselves. "No one enjoys playing it," said Donovan Hunt, known as Tekkz, in February — of the game in which he is a top-ranked player. Forums like Reddit vacillate between outright disdain for the game and pleading to the possibly-watching EA devs for more content. Gamers with gripes are nothing new, and Ultimate Team complaints can be as basic as persistent server connectivity issues or irritating bugs. But among them there's a curious self-awareness of the players' own inability to stop doing something they say they don't want to do. A typical gallows humor response to an anti-EA screed might simply refer to the season's restart: "See you in October."

The distress from fans extends across EA's titles. Madden NFL 21, EA's other 'football' game, garnered one of the lowest Metacritic user scores of all time upon its release in August. It still ended up the best-selling game in the US that month according to The NPD Group.

Two things are clear: A vocal contingent of both pros and casual players dislike FIFA Ultimate Team. Yet they also keep playing it in droves. Someone who knows this contradiction well is Jonathan Peniket.

Peniket was 12 years old when he first bought a pack. Growing up in Hertfordshire, just outside of London in the U.K., he'd spend no more than £200 ($260) on packs in each cycle of FIFA in the years that followed, he said.

A football fan and capable FIFA player, Peniket followed YouTubers like AA9skillz, MattHDGamer and KSI. He needed to purchase the player packs, he said, to keep his team competitive in a game his friends also played. "The pay to win aspect is absolutely huge," Peniket told Engadget. "You'll know that if you spend more money on packs your team will be better."

The turning point came when Peniket was in his final year of secondary (high) school. By this time, he had a debit card. That meant potential access to impulsive, frictionless spending on his PS4. Previously, he'd have to buy physical PlayStation Store vouchers from UK retailer HMV and furtively hide them from his parents between the pages of books.

This was also the year his mother was diagnosed with cancer, only the year after a friend had also passed away. Now, Peniket barely played a match of FIFA, but spent hours opening loot boxes every day. In the family's spare room, he was dropping £20 per sitting, then £30, £40, up to £80 — four or five times a night. "The time when I spent the most money was probably one of the times when I was playing [the fewest] actual games of FIFA," he said.

"You can always, always chase something better." - Jonathan Peniket

Peniket wasn't addicted to FIFA. Instead, he said he was addicted to opening packs. The "buzz of chance," as he put it, around potentially unveiling a top player. It was a reliable rush for him, a soothing mechanism when life otherwise seemed miserable. He obsessed over fine-tuning his team on websites like Futhead and Futbin — popular for their databases detailing players' stats — over revising for the exams that would get him into university. At one point he downloaded a third-party pack-opening simulator onto his phone.

The game seemed endless. No matter which players popped out of his packs, the game always released another better one, so his team was never complete. The high of a lucky draw never lasted long enough to stop him putting down more cash. "You can always, always chase something better," Peniket said. "There was never 'oh, I'm just spending until I get to this point.'"

The guilt built up and the money ran out. Peniket told his mother one night he thought he'd spent £700 on the game. His parents looked up the statements and it turned out he had spent £2,700 — savings that included money gifted from his granddad, a church worker, as an 18th birthday present. His mother told him he'd broken her heart. “Hearing that broke my heart," he said. Peniket didn't tell anyone else about this for a year.

‘Pay to lose’

The fundamental way Ultimate Team compels the player hasn't changed in more than a decade.

To populate a digital dollhouse of sportsmen, you not only open packs to find players but can buy and sell them on a virtual transfer market. The funds to buy said cards are accumulated by playing games and playing them better than everyone else on Ultimate Team each week. Play well enough for long enough and one can qualify for weekly tournaments which beget bigger rewards and hence stronger teams.

At its most enjoyable, Ultimate Team can be about "sniping" a rare deal off the transfer market, finding a fresh way to match the "chemistry" of your players (players get bonus stats when lined up adjacent to players of the same nationality or league) and setting up a personally sentimental team of past-and-present legends (say, Steven Gerrard playing with Mohammed Salah and Kenny Dalglish). At worst, it's a football-themed Skinner box, a grind for each shiny new player the second it’s released, with every user eventually gravitating to the same few overpowered squad members and strategies — or a dry simulator of transfer market investments and trades.

The matches themselves play out like any other FIFA game — the mechanics of which one can quibble over for improvements but is generally the best it gets right now. What differentiates Ultimate Team from the rest of FIFA is the structure it's housed in, its reward system. It's the most noticeable difference in how the game feels to a new player.

That feeling is like stepping out of a polished, premium title and into the kind of free-to-play mobile game with which you expect — and adjust your expectations to allow — a more mercenary experience.

The question of how FIFA — a game so popular that real-life football pros play it to scout their upcoming opponents — could improve its basic gameplay is actually far more interesting when you look beyond the series-defining Ultimate Team mode. One might hope that the next generation of consoles — which FIFA 21 will later release on — could provide the impetus for an engine update which hasn't been meaningfully improved for years.

Some fundamental questions for a faithful football simulator: How do you make defending, which is more about anticipation and collective action than a single moment of drama, as interesting as attacking? (The legendary Italian defender Paolo Maldini is often quoted as having said: "If I have to make a tackle then I have already made a mistake.")

For that matter, how do you even make shooting — the most dramatic inflection point in a match — a gameplay event more nuanced than holding a button and a single direction. One point of controversy in recent game cycles has simply been how to make scoring close-range headers — in real life technically and physically challenging; in FIFA a mere button press — viable but not overpowered.

Essentially, the question of how to translate an 11-a-side game that depends both on team-wide coordination and individual brilliance into a simulation played by one puppet master on a couch has yet to be cracked. FIFA's Pro Clubs mode allows eleven different players to each control their own avatar, but it's long been neglected by developers, plus requires ten available friends for a match. FIFA 21 has tried to address this mechanic for individual players in one small way by allowing players to direct off-the-ball runs but it’s yet to be seen whether this is a lasting feature or one of many annual experiments with game mechanics.

Ultimate Team feels different because the incentives are different. The goal of the corporation that publishes Ultimate Team is not for the player to have a top time and hopefully drop another $60 next season, it’s to entice them to pay up regularly. So the games use the kind of hackneyed freemium game design principles known for being addictive past the point when they stop being fun.

One signature of a compulsive game is the overuse of variable rate enforcement — essentially a reward given randomly which floods the brain with more dopamine than a reward doled out on a steady schedule. Psychologists have shown that we love when we think we're getting lucky.

Add the principle of scarcity: what's rare is valuable. The prospect of landing impossible-to-find players like Neymar will keep players rolling the dice. But so will time-limited "events" where new, special cards are on offer — what EA's Jorgensen called "the secret sauce" in Ultimate Team at a 2017 NASDAQ investor's conference.

Not everyone buys loot boxes with real money, but in that same discussion, Jorgensen said that about half of Ultimate Team players across EA Sports' games do. The ability to purchase loot boxes allows players to progress faster and skip the grind of gameplay if they spend more money. It's "sweat versus cash equity," as a creator of FIFA Ultimate Team once put it. This clearly plays out with sponsored eSports players who might get a five-figure budget to boost their teams at the start of each season — something one German pro at FC Schalke notably declined this season.

If you do choose to spend money? First, you convert dollars into FIFA "points." Like buying poker chips at a casino, this obfuscates the amount of real money you're spending on each transaction, making it easier to part with.

"A lot of techniques, tactics and tools that go into loot boxes are based on gambling, industry, learnings and findings," said Keith Whyte, executive director of the National Council on Problem Gambling. "We've seen gambling mechanics become clustered together into the epitome of it, which is a loot box."

What matters most in Ultimate Team is still your skill in matches and your knowledge of the transfer market, says Ben Salem, content lead at major Ultimate Team website Futhead who also hosts the podcast FUT Weekly (FUT is an acronym for FIFA Ultimate Team). “Although you can help yourself a lot by spending FIFA points, you're not just going to pay to win. In fact, it's become a bit of a joke in the community that people pay to lose,” he said. Spending cash in-game can confer an advantage, but not a guarantee of success.

This is the awkward line EA tries to walk with loot boxes. The game has to be viable for those who aren’t spending any money on microtransactions, but still make players who choose to spend feel they got some bang for their buck.

Allowing users to spend money only on random packs, not individual players, prevents high-rollers from splurging on the best team in the game, making it an unpopular “pay to win” title for everyone else. Yet the lack of a guaranteed outcome when you buy a pack, is also the psychological mechanism that makes loot boxes addictive, encouraging people to try repeatedly to hit the jackpot. What would be more obscene: a game that allows you to pay $1,000 to play as Cristiano Ronaldo, or one where you might spend $1,000 and still have no Cristiano Ronaldo?

Even if you clinch the card you want, the fantasy of owning your perfect team is ultimately illusory, or at best temporary. Better cards are constantly released and you can fall behind other players on the "power curve" if you don't keep up. Then, by the time you've gotten an overpowered, 95-out-of-100-rated all-star roster, it's September and this year's game is over. Everyone stops playing the game en-masse, objectives and events disappear and there's nothing to play for anymore.

'A sense of pride and accomplishment'

EA hardly pioneered the tired techniques that cajole microtransactions out of gamers. But it might have done more than any other major publisher to bring them to a mainstream, premium price console game.

After originating in Asia — first in Chinese games like ZT Online and then in mobile games across the region — it was the rise of smartphones in the West that established free-to-start games as a norm. PC games like League of Legends and World of Tanks picked up the format as it became the fastest growing segment of the gaming industry at the time.

This time period coincided with the tail end of the PS3 and Xbox 360 generation of consoles. As developers looked to the next wave of very-online gaming machines, the big question was how would they keep gamers continuously spending after they'd shelled out the cover price of a title, said Gee from Bank of America Merrill Lynch. According to Gee, EA's profit margins hovered around four percent at the time.

After experimenting with the Ultimate Team concept in the Xbox 360 version of UEFA Champions League 2006–2007, a standalone title, EA pushed it as a $10 add-on in 2009 for FIFA 09.

It made $10 million in its first six weeks and more FIFA players were online than ever before. Peter Moore, then-president of EA Sports who later became CEO of a resurgent (and non-virtual) Liverpool Football Club, called EA's pivot to online gaming a "radical shift that we've helped pioneer in the industry."

Microtransactions, downloadable content and other "live services" as EA termed them, became the company's fastest growing business. Four years after its full debut in FIFA 09, Ultimate Team was part of every EA Sports franchise including Madden NFL, NBA Live and NHL. Andrew Wilson, who had overseen FIFA as Ultimate Team was blooming, became CEO of EA, a title he holds to this day.

"I feel that once Andrew Wilson took the CEO role, his expertise in that mechanism and the ability to grow that business actually filtered down into other areas of business beyond sports," said Gee. "I think you can attribute a lot of what you see in EA's business today, in terms of the in-game mechanisms, to Ultimate Team back in 2009."

"Everybody wants revenue where a player every single day logs in and plays the game" - Michael Pachter

EA was now implanting this business model in all genres of games: mobile strategy game Dungeon Keeper, racer Need for Speed: Payback, RPG Mass Effect 3. The company was hardly alone — in Counter-Strike: Global Offensive and Team Fortress 2, Valve was visibly looking for the same formula. And it was clear why. Microtransactions, add-ons, in-game events — all of these were cheaper to produce than developing new AAA titles from scratch, and they provided the kind of predictable, regular revenue that investors love.

"Everybody wants revenue where a player every single day logs in and plays the game," said Michael Pachter, an analyst and videogames expert at Wedbush Securities. "That's the most predictable basic model. The reason that Starbucks has value is because it's a habit, people go there every day."

Ultimate Team runs in tandem with global football seasons, its in-game events mimicking the peaks and troughs of players' performances in real life. Crucially, EA has a captive audience in FIFA because it holds the license for most of the world's major football clubs, with only a few exceptions. That means only EA — and not its closest rival Konami, which makes Pro Evolution Soccer — can publish a game with the most authentic kits, badges, stadiums and team names. That reason alone is enough to guarantee a steady demand for FIFA, just as it does with EA's officially licensed Star Wars games.

“There isn't a small games company that is run in a way that people prefer that could afford to buy those rights from FIFA,” said Salem from Futhead, referring to football’s global governing body which licenses its own name and tournaments to EA for the game. “So essentially, it's always going to be the biggest, wealthiest, probably most powerful and — in some way — institutional gaming company that owns the rights to football. And that is EA.”

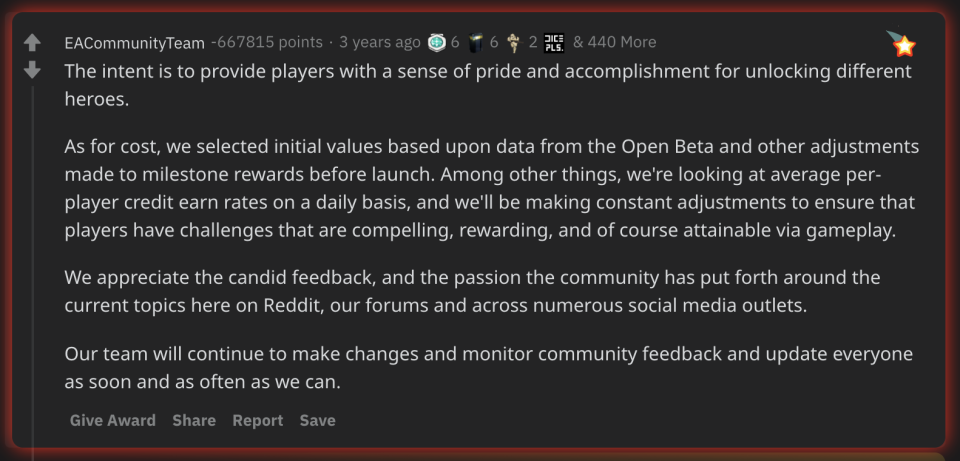

By 2016, EA was making about $650 million a year from Ultimate Team. But in tandem with these boom times, something else was happening. In 2013, EA was named "worst company in America" for the second year in a row by The Consumerist. After the peak of consumer backlash against EA's loot boxes in Star Wars: Battlefront II, the company earned the ignominious distinction of a Guinness World Record for the most downvoted Reddit comment in history as it struggled to justify its game design as providing "a sense of pride and accomplishment." Fast forward to 2019 and EA was jeered yet again for telling a UK Parliamentary committee that their loot boxes are "surprise mechanics" like Kinder Eggs which are "actually quite ethical and quite fun."

Cumulatively, EA has garnered a reputation as a nakedly bottom-line driven publisher. Being at the top of an industry tends to put a target on one's back, and overblown pearl clutching has often followed game makers. But just how vocal gamers have been against microtransactions and the publishers that push them is unique, says Cam Adair, the founder of Game Quitters, a support group for gaming addicts. "Typically, the gaming community is very defensive about their games and about their industry," he said.

The idea of paying to win is inherently offensive if you play games; fair competition is a basic assumption of any game. Microtransactions — especially in a game you're already paying to own — might feel like a corporate intrusion on the closed respite of the game world.

"It's the game company against the gamer," said Adair, "whereas traditionally they were on the same team."

There is very little business incentive for EA to change its reliance on loot box monetization right now. The potential levers to change that are regulatory pressure, legal pressure and public pressure.

The U.K. government recently launched a call for evidence on loot boxes after a group from the House of Lords recommended they be regulated as gambling. In the U.S., loot box state legislation has been in the works for years — in Hawaii, Indiana, Minnesota and Washington among other areas — but development has stalled this year amidst a pandemic and political instability. But a string of class-action lawsuits in California are challenging not just EA but Supercell, Activision, Apple and Google (the latter two for selling loot box games through their app stores), while EA is also facing court battles in France and Canada. Another lawsuit in California alleges AI difficulty adjustment makes players perform worse than they should in Ultimate Team to incentivize buying packs (EA denies the claim).

Yet the winds of public opinion are already clear. Overwatch and Rocket League have shifted their microtransaction methods away from unpopular loot boxes as battle passes gain popularity. Games like Fortnite and Call of Duty: Warzone sell cosmetic items over performance-enhancing ones, sidestepping the pay-to-win controversy altogether.

Christopher Hansford, political engagement director at Consumers for Digital Fairness, which advocates against loot boxes in gaming, says that regulatory pressure in enough jurisdictions — such as the ban in Belgium where EA can no longer sell Ultimate Team packs for money — could lead EA to preemptively change their monetization method altogether. "I don't think that EA has the capacity or the interest to try to roll out different models of their product in different states to try to comply when they can make a core product from the ground up that everybody can buy," he said.

One recent concession from EA is the introduction of a “Playtime” tool, not dissimilar to Apple’s “Screen Time” feature on iPhones. Playtime allows parents and players to set limits on both time and money spent in FIFA.

But it doesn’t alter the core game incentives. The core question remains what would Ultimate Team look like without paid packs? FIFA has experimented with introducing non-paid cosmetics into its 'Volta' futsal mode and stadium customization in Ultimate Team but the awkward issue is that those aesthetics likely do not incentivize FIFA players to spend the way a rare, playable Kylian Mbappe card can.

Rivals

On YouTube and Twitch, videos of men joyously opening pack after pack in Ultimate Team are an entire genre.

The in-game animation itself is all flashing sparks and delayed gratification. The nationality, position then club of the revealed player flash on screen like cherries in a slot machine, before the final reveal of your received player. Get an Argentinian right winger that turns out to be Lucas Ocampos and you might feel you were close to getting Messi — then try again.

It's no coincidence that Peniket spent his time watching YouTube pack openings when he was most addicted to buying them himself. It felt almost aspirational: if only I had this many packs to open. Yet watching streamers pull their dream cards also makes them feel attainable. EA's disclosed odds of replicating these moments, however, are low — special cards usually appear less than one percent of the time.

"It's the sense of euphoria in the game that you're chasing yourself," Peniket said. "Ultimately you go on to seek to replicate those results yourself. It's what you yourself are dreaming of achieving in the game."

Peniket is far from the most cautionary example of unchecked loot box spending. One UK-based FIFA Ultimate Team player in his thirties told Eurogamer he'd spent over $10,000 in two years on the game, which he only realized when he submitted a GDPR request to EA for his personal data. A Bleacher Report survey from last year found users estimating FIFA spends in the six-figures.

The University of York's David Zendle has established significant links between loot box spending and problem gambling — though it's unclear if one is causing the other or the two are merely related.

The question of whether loot boxes are legally considered gambling will depend on the jurisdiction. But in the U.S., much has centered on game publishers arguing that loot boxes are not gambling because you can't cash out your winnings in real legal tender, and therefore they have no real value.

Even if you ignore the existence of black market websites that buy or sell FIFA coins (the in-game currency you win for playing matches), that argument is disputed by Timothy Blood, managing partner at Blood Hurst & O’Reardon, which is currently suing EA in California. "People are actually paying real money to obtain something that the loot box offers," he said. "And so, by definition, they're paying money to receive something of value."

In fact, the idea that Whyte, whose organization the National Council on Problem Gambling has examined problem gambling since the 1970s, is concerned with loot boxes is a strong sign of their connection. As is the fact that Peniket, after first retelling his story of addiction on his friend's YouTube channel and then to the BBC, has just been hired as a consultant on gaming and eSports to EPIC Risk Management, which advises companies on preventing gambling harm.

Especially damning was Epic Games CEO Tim Sweeney's speech in February this year. "We have to ask ourselves, as an industry, what we want to be when we grow up. Do we want to be like Las Vegas, with slot machines ... or do we want to be widely respected as creators of products that customers can trust? I think we will see more and more publishers move away from loot boxes," he said. “Loot boxes play on all the mechanics of gambling except for the ability to get more money out in the end.”

In a statement to Engadget, an EA spokeswoman said: “We firmly believe that nothing in our games constitutes gambling in any way.” It emphasized that FIFA Ultimate Team can be played without spending real money, calling the use of packs “dynamic and exciting.”

Yet put aside for a moment the binary question of whether loot boxes can be pigeonholed as gambling or not. Much of the tech industry’s rush to gamify their UX flirts with the line between “engagement” and exploitation, whether in stock trading apps or Twitch hype trains. Those gamification techniques have been ploughed back into games. "These digital products are optimizing themselves using persuasive psychology to make money," said Adair of Game Quitters, a former gaming addict himself. "Lots of people put lots of hours into analyzing the data, and understanding the user behavior, and then manipulating that data in order to try to make money."

For Zendle, too, this is the core issue that the microtransactions debate has surfaced. There has been a fundamental shift in how games are monetized and how user data can inform those selling practices in real time. Lawmakers and regulatory bodies find it hard enough to understand them, let alone ensure they’re not exploiting players.

"Lots of people think the fire is the loot boxes but I think the fire is the systematic change in how games are made that led to loot boxes," Zendle said. "Where do purchases become fair or unfair? If you're using my data in-game to change how I play so you can make me buy different things for real money, is that unfair? Is that worthy of regulation?"

"Lots of people think the fire is the loot boxes but I think the fire is the systematic change in how games are made that led to loot boxes" - David Zendle

For instance, the CEO of Yodo1, which made the mobile Transformers game, told a gaming conference last year that a player had spent $150,000 in microtransactions. The company is now using AI to identify the heavy-spending "whales" to induce them to spend more, he said. "By being able to predict who they're gonna be, we can then start to analyze how to keep them in the game [and] analyze their behavior," he told the audience. "How do I increase their sessions? How do I increase their session times? How do I gently present to them a very attractive in-game bundle that is going to help them stay in the game?"

Laws and policies almost always lag behind the pace of technological change. See, for example, governments straining to determine what exact labor rights an Uber driver has. Gambling, meanwhile, is a well-understood phenomenon. Tying loot boxes to the concept allows governments to both comprehend its impact on citizens and fit it into a pre-existing regulatory framework.

In FIFA, the matches themselves can still be fun, dramatic and strategic. But Ultimate Team? There's a point at which the card-swapping, the niche objectives, the fleeting rewards, they all feel more compulsive than enjoyable. Like instead of the match being the most important thing, it's all the box-checking busy work that’s driving the experience.

Then again, the idea of a football video game where a reliable way to accrue an advantage is to pour illogical amounts of personal wealth into the adept trading of human labor is an all-too-apt representation of the real-life global football industry today. The billionaire owners of mega-clubs are really just engaged in an advanced form of "pay to play." In this way, Ultimate Team might be ultimately realistic — both a product and simulator of modern sports capitalism — but both the game and the reality it represents could leave fans feeling dirty.